Turn the lens on you. Image by Flickr user Jeremy Schultz.

On my way home from work this evening, I caught a piece on NPR about a manifesto for women that’s been laid out by a brigade of fighters for the Islamic State. The manifesto is surprising for a number of reasons, chief among them the fact that its authors are themselves women. But perhaps the biggest kicker in its text is the statement that “It is considered legitimate for a girl to be married at the age of nine.”

Nine.

This is in the same manifesto that also encourages men to “rise above harming women and criticise those who do, detract against and vilify them.”

For a blinding moment, I was absolutely appalled by the utter hypocrisy of those two statements. Men should not harm women, but they can marry (Read: Exploit at all levels.) pre-pubescent girls? How is that at all acceptable?

After a few deep breaths, though, I had to remind myself of the realities faced by women in extreme religious environments in my own country.

I’ve worked with clients who were married off to middle-aged men and expected to be their sexual partners at even younger ages than the al-Khanssaa manifesto recommends. At least two states permit girls to get married at age 12 (or younger) if they have the permission of their parents and the courts. And, of course, the United States loves to celebrate Christopher Columbus every year, who not only led the campaign to pillage a continent but enjoyed prostituting pre-pubescent children to his men as “rewards.”

In short, I had to remind myself that hypocrisy is nothing new, anywhere in the world.

Global citizens and activists often run afoul of this basic tenet of humanity. We tend to condemn as barbaric that which we ignore in our own culture; we happily point out the flaws we see in other cultures while envisioning our own as perfect or, at least, more ideal. At the same time, when confronted on this shortcoming of ours, our (legitimate) response is to demand why we should show respect to practices and beliefs that are clearly, by our standards, unacceptable. “After all,” we say, “anyone else who partnered with a nine-year-old would be called a pedophile.”

Which is true, where I come from.

So how do we strike a balance between calling for an end to human rights injustices and respecting the boundaries and worldviews of cultures that differ from our own? I don’t claim to be perfect, but here are some thoughts:

Consider the voices that are participating in the debate.

Does your voice reflect power, privilege, and/or a worldview that’s already very dominant? Is there someone else who may have more of a right to speak up than you?

For example: Are you participating in a conversation about ways to end child sexual enslavement around the world, or are you telling someone from another part of the world how to fix “their” problem? The rules of being an ally apply here. By the same token, however, are you speaking for someone who doesn’t fully have a voice yet, like a child?

Set standards that represent parity, not a one-size-fits-all approach.

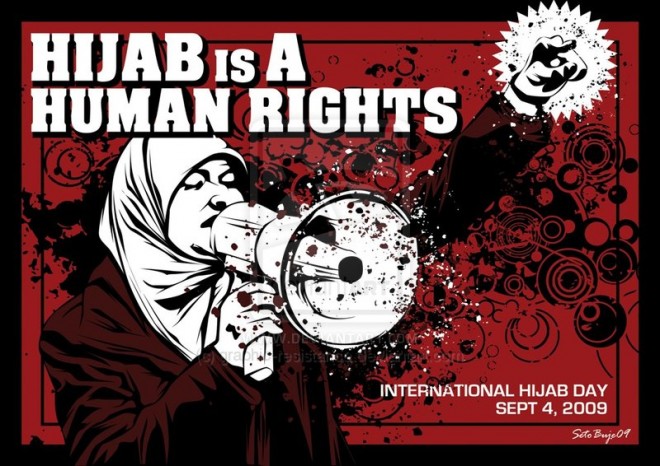

“Equality” has often meant setting one standard for everybody, which may or may not be achievable or culturally appropriate — i.e. denying Muslim women the right to wear hijab while claiming it’s an equal standard for people of all faiths. When working to find a solution to a global problem, focus on ways to develop standards that are inclusive of, and respectful towards, all voices. At the same time, be uncompromising of humanity’s basic rights.

How do we define human rights for, and with, each other? Image from deviantart.com.

Distinguish between systems of power and systems of belief.

It’s easy to get caught up in a tide of Islamophobia or the belief that religion is the root of all evil. These, and similar vilifying lines of thought, don’t help anyone. Religion and belief are key components of many peoples’ life experiences and cannot be discarded because we find them unpalatable.

What becomes problematic is the use of belief systems, by people in power, as tools of oppression and domination. This is where our debates must focus if we want to collaborate for lasting change.

Address the problems inherent in our own cultures before trying to address anyone else’s.

We can condemn the denial of education to women, female genital cutting, or the representation of women as sex objects all we want, but we have to be prepared to look at the role our home cultures play in permitting these behaviours. If I want to condemn the al-Khanssaa perspective on child marriage, I have to condemn the abuse of the United States’ freedom of religion clause by Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS) sects as well. I don’t have to pretend that one issue is identical to another, or more prevalent than another, but I do have to be honest.

Avoid reducing a debate to name-calling.

“Barbaric,” “primitive,” and “sub-human” might be tempting labels to apply to practices or beliefs that don’t jive with our own, but they get us nowhere. The second we set our home cultures on some sort of pedestal or claim some form of superiority, we end the discussion and perpetuate the divisions that have been plaguing us for most of human history.